This post was published in the Common Craft Newsletter. Subscribe here

When explaining an idea, thinking about "dumbing it down" or "explaining like I'm five" seems like the right path. These approaches have a place, but I don't think they are productive. Why? Because they come with a significant risk.

There is a silent killer of explanations that always lurks in the background. Despite our best intentions, it can sully the best explanations and cause the audience to tune out. The killer is condescension. When our audience detects it, they may stop listening altogether.

Why?

When someone is condescending, they communicate with an air of superiority and even disdain. It's the "Behold, I am the expert and you shall now learn from my wisdom" kind of feeling. We've all felt it and it's not fun.

This is a risk for explainers because explanations inherently involve a knowledge mismatch. By explaining an idea, I am assuming I know something that you don't. This is fertile ground for condescension and awkward situations.

This is why the idea of "dumbing it down" or "explaining like I'm five" can be counter-productive. These approaches default to the lowest level of knowledge. They assume that people are not intelligent enough to understand what others can easily grasp. If this is your starting point for an explanation, it's likely to sound condescending.

Two Ideas to Keep in Mind

The question becomes... how do I avoid sounding like a condescending jerk? Here are a couple of strategies.

Keep it Familiar

Explanations are social because they involve an audience. The success of an explanation depends on the audience's perception of the communication. If it works for them, it works.

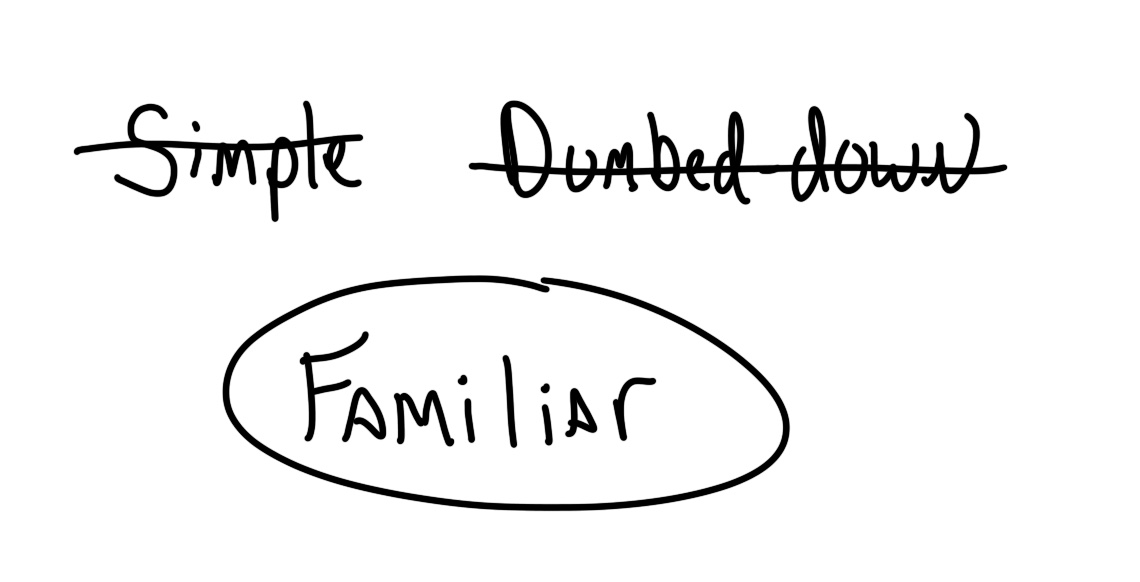

When we think in terms of simplicity, or dumbing down, it's a one-size-fits-all approach. This is what can lead to a feeling of condescension.

I recommend thinking instead in terms of familiarity. What is going to be familiar to the audience? What examples and language are going to respect the audience's existing knowledge? By making familiarity the priority, we can ensure that our explanations are well received.

Assume Intelligence

In an interview, science writer Steven Pinker said this about finding the right approach:

Before I wrote my first cognitive book, I got a bit of advice from an editor, which was probably the best advice I ever received. She said that the problem many scientists and academics have when they write for a broad audience is that they condescend; they assume that their target audience isn't too bright ... and so they write in motherese, they talk down. She said: "You should assume your readers are as smart as you are, as curious as you are, but they don't know what you know and you're there to tell them what they don't know." I'm willing to make a reader do some work as long as I do the work of giving them all the material they need to make sense of an idea.

I think this is phenomenal advice. There is a big difference between a lack of information and a lack of intelligence. To avoid condescension, assume intelligence and provide information.