This post was published in the Common Craft Newsletter. Subscribe here.

The first Common Craft videos came from seeing technology experts stumble through explanations of social media. I thought, "That's not going to help anyone". I sometimes feel like an early warning system for poor communication because I am naturally drawn to (and need) clarity. I can empathize with the confused and bewildered and work to account for their needs.

In fact, I believe the majority of people are underserved when it comes to clear communication. I worry that people are needlessly left behind because of the disconnect between expertise and clear communication. That's part of the magic of being an explainer: helping people develop a clear understanding of something new.

Think about it this way...

We need experts who are qualified to speak about their fields. Unfortunately, expertise and clear communication do not always work together. The expert's deep knowledge and experience influence how they communicate and can limit the reach of their words. Like many of us, they have the curse of knowledge and are prone to using acronyms, jargon, and examples that require context and experience.

For too long, access to this kind of expertise was limited to classrooms and textbooks. Educators were (and still are) on the front lines of translating complicated language and information into lessons that are clear and understandable. This is vital, but still represents only a slice of the population who could be learning.

The question is: how does everyone else learn? Who is accounting for the huge number of people who are out of school and just want to learn something new?

To me, that's the role of the explainer. We're not experts in specific domains like medicine or law. Our expertise is in clear communication and creating resources for people who need help getting up to speed. We learn about and understand a subject in order to translate it clearly. Then we move to the next subject.

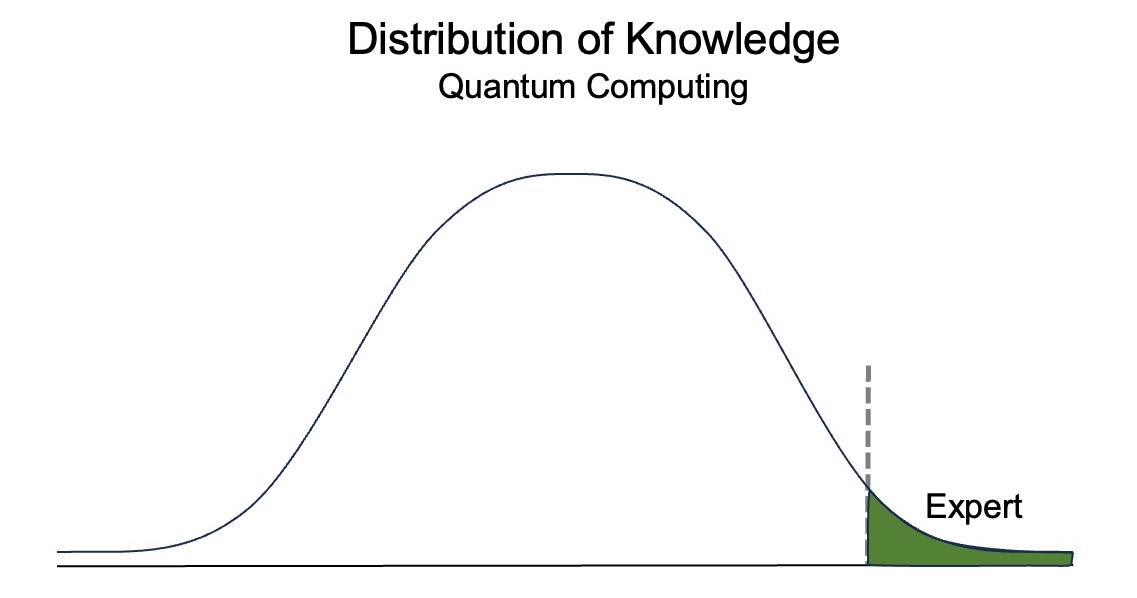

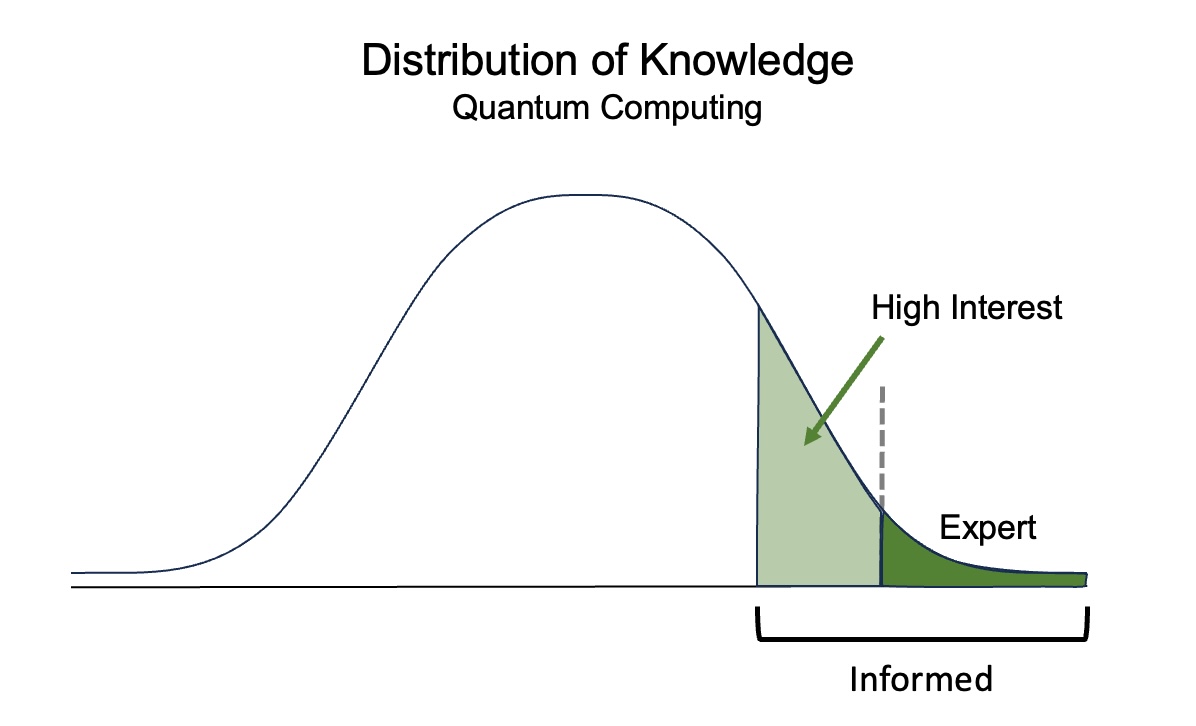

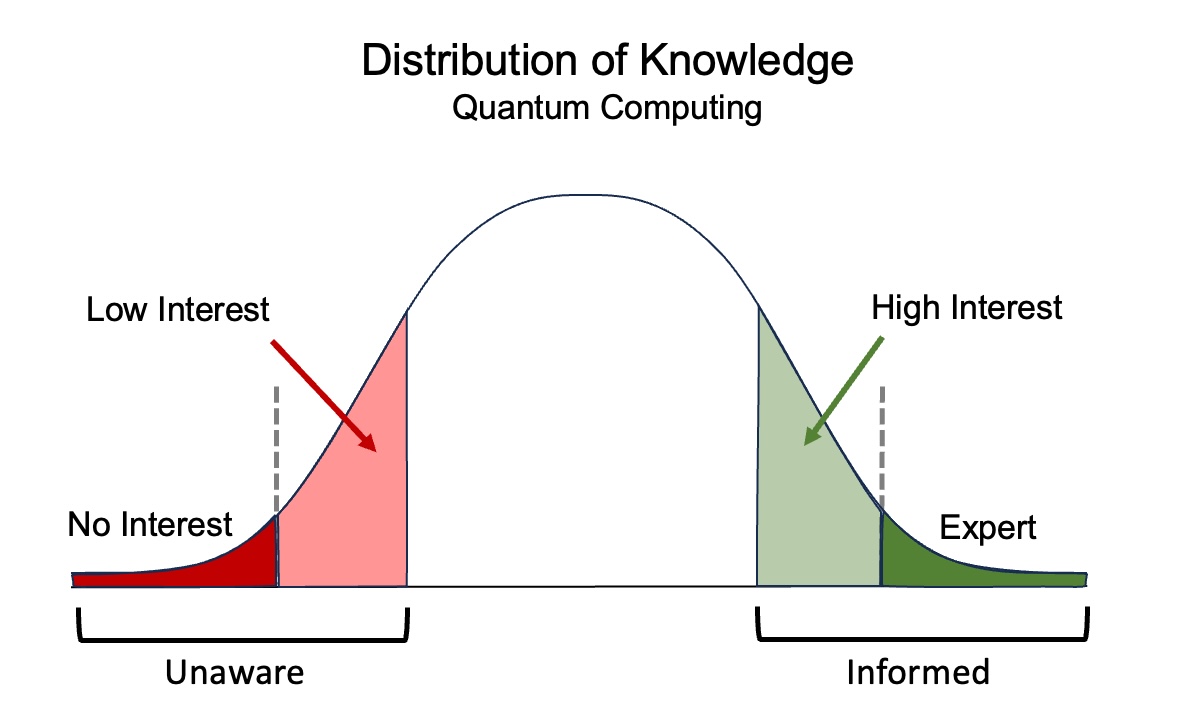

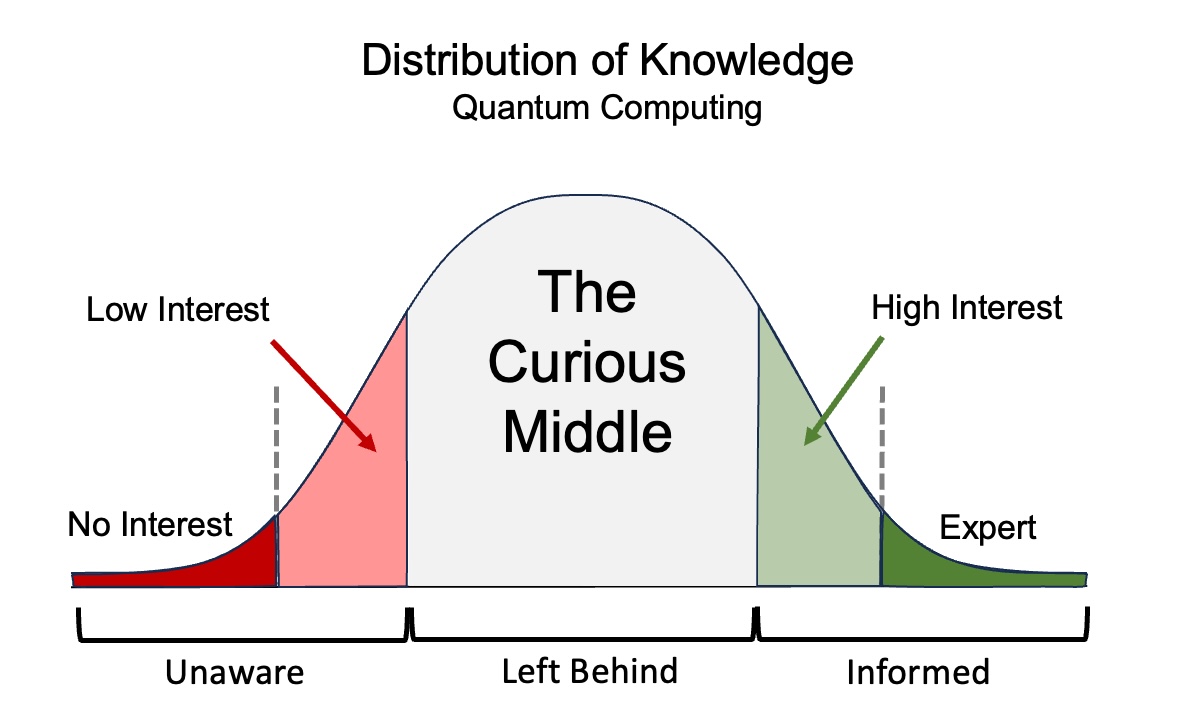

Let's consider an idea like quantum computing. The knowledge of quantum computing is varied and we'll assume the distribution takes the shape of a normal curve. On the right side of the curve, we have a relatively small population of experts who know enough about quantum computing to do presentations and write articles. What we know about the subject comes from them.

Next, we have a bigger population that's interested in quantum computing and excited to learn from the experts. They know enough to keep up and are motivated to seek out information. This population is informed and working toward expertise. Some may be educators.

On the other side, we have the unaware and disinterested. We won't worry about them for now.

Then we have the biggest group of all: the curious middle. This group is aware of quantum computing but has very little knowledge. They're capable of understanding it, but only when it's explained in ways that account for their familiarity. Without help, they may be left behind.

When I think about my work as an explainer, I'm focused on the curious middle. This large population is unfortunately underserved because they need the right kind of introduction to an idea. Experts can help, but their focus is often growing their expertise and pushing the envelope.

Explainers don't have to be experts in quantum computing to help. In fact, true expertise in a single subject may compromise our ability to explain it clearly. Instead, we are experts in the process of understanding our audience's needs and developing useful resources for them.

When I think about my work at Common Craft, Explainer Academy, and The Art of Explanation, I'm focused on helping the curious middle and I can't do it alone. To help them, we need more explainers. We need people who are ready to take on the challenge and create resources that can help.

This summer, think about the idea of the curious middle and what explanations you could develop to help people who are being left behind.